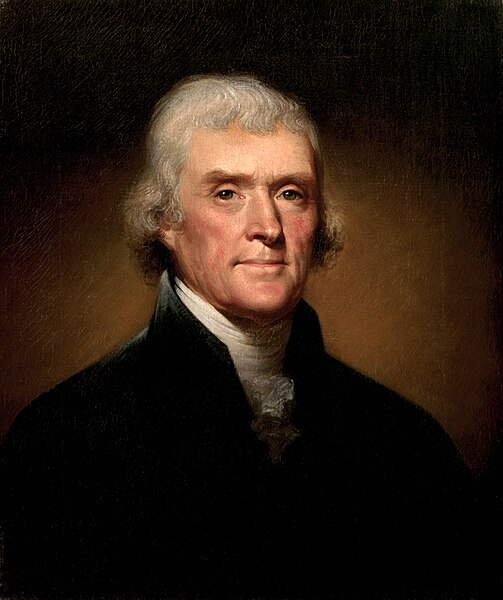

On May 25 1812, Thomas Jefferson is also writing to James Madison. He is passing along letters from a number of persons who want positions in government. Jefferson also provides information on various products as as result of the embargo. He notes that the price of flour is rising but that the cultivation of tobacco is being abandoned. As for war, Jefferson writes: "Your declaration of war is expected with perfect calmness; and if those in the North mean systematically to govern the majority it is as good a time for trying them as we can expect."

Dear Sir Monticello May 25. 1812

The difference between a communication & sollicitation is too obvious to need suggestion. While the latter adds to embarrassments, the former only enlarges the field of choice. The inclosed letters are merely communications. Of Stewart I know nothing. Price who recommends him is I believe a good man, not otherwise known to me than as a partner of B. Morgan of N. O. and as having several times communicated to me useful information, while I was in the government. Timothy Matlack I have known well since the first Congress to which he was an assistant secretary. He has been always a good whig, & being an active one has been abused by his opponents, but I have ever thought him an honest man. I think he must be known to yourself.

Flour, depressed under the first panic of the embargo has been rising by degrees to 8½ D. This enables the upper country to get theirs to a good market. Tobacco (except of favorite qualities) is nothing. It’s culture is very much abandoned. In this county what little ground had been destined for it is mostly put into corn. Crops of wheat are become very promising, altho’ deluged with rain, of which 10. Inches fell in 10. days, and closed with a very destructive hail. I am just returned from Bedford. I believe every county South of James river, from Buckingham to the Blue ridge (the limits of my information) furnished it’s quota of volunteers. Your declaration of war is expected with perfect calmness; and if those in the North mean systematically to govern the majority it is as good a time for trying them as we can expect. Affectionately Adieu

Notes

Cite as: The Papers of James Madison Digital Edition, J. C. A. Stagg, editor. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2010.

Canonic URL: http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JSMN-03-04-02-0444 [accessed 30 Dec 2011]

Original source: Presidential Series, Volume 4 (5 November 1811–9 July 1812 and supplement 5 March 1809–19 October 1811)

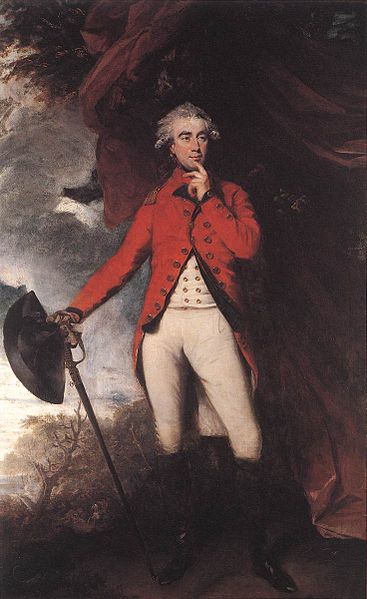

On May 31, 1812, Lord Moira is trying to form a government having been given some indication that he should try to do so by the Prince Regent. Moira is an Irish-British politician and a Whig. He favours Catholic Emancipation but may, at this time, be willing to compromise on that point. He writes to Lord Grey, another prominent Whig, to confirm exactly what he said in the House of Lords. Grey receives the letter while having dinner at Holland House but responds immediately. He writes that he cannot remember the exact words he used but confirms that in substance certain pledges on Catholic Emancipation had been made. He does not say who made the pledges but implies it was the Prince Regent. Grey writes that as a consequence if the Prince Regent feels "a strong personal objection" to him then he is prepared to "stand out of the way." He would still support a Whig government. The maneuverings are of interest in that they indicate that the Crown still had a determinative role as to who would form the government. A Whig government may have had a different American policy but by now it is too late to stop an American declaration of war. Madison is putting the final touches on the secret message that he will be sent tomorrow, June 1, to Congress proposing war with Great Britain. Moira's letter is reproduced below followed by Grey's response:

On May 31, 1812, Lord Moira is trying to form a government having been given some indication that he should try to do so by the Prince Regent. Moira is an Irish-British politician and a Whig. He favours Catholic Emancipation but may, at this time, be willing to compromise on that point. He writes to Lord Grey, another prominent Whig, to confirm exactly what he said in the House of Lords. Grey receives the letter while having dinner at Holland House but responds immediately. He writes that he cannot remember the exact words he used but confirms that in substance certain pledges on Catholic Emancipation had been made. He does not say who made the pledges but implies it was the Prince Regent. Grey writes that as a consequence if the Prince Regent feels "a strong personal objection" to him then he is prepared to "stand out of the way." He would still support a Whig government. The maneuverings are of interest in that they indicate that the Crown still had a determinative role as to who would form the government. A Whig government may have had a different American policy but by now it is too late to stop an American declaration of war. Madison is putting the final touches on the secret message that he will be sent tomorrow, June 1, to Congress proposing war with Great Britain. Moira's letter is reproduced below followed by Grey's response:

-2.png)

.png/220px-Portrait_of_H_Crabb_Robinson_(crop).png)

-2.png/220px-Isaac_Brock_portrait_1,_from_The_Story_of_Isaac_Brock_(1908)-2.png)