On June 30, 1812, Jonathan Russell, the American diplomat in London, writes to James Monroe about the repeal of the Orders in Council. Russell describes how the government had to give way on the issue. He writes: "Many members of the House of Commons, who had been the advocates of the orders in council, particularly Mr. Wilberforce, and others from the northern counties, were forced now to make a stand against them, or to meet the indignation of their constituents at the approaching election. It is, therefore, the country, and not the opposition, which has driven the ministers to yield on this occasion; and the eloquence of Mr. Brougham would have been in vain had it been destitute of this support." Russell's letter is reproduced below.

June 30 1812: Death of the Horses

On June 30, 1812, the rain continued to fall near Vilna but the full force of the storm had passed. Colonel Boulart of the Artillery of the Guard had passed the night under a gun carriage. He would recall [1]:

The fourth Bulletin De La Grande Armée dated June 30, 1812 says nothing of the deteorating situation and is reproduced below.

By daybreak, the storm had passed but it was still raining. What a sight offered to my eyes! A quarter of my horses were lying on the ground some dead or dying, others shivering. I quickly ordered as many as possible to be harnessed, hoping to get my wagons away, and to set this sad crew in motion so that the poor creatures might generate some of the heat they so badly needed, and thereby prevent a good number of them dying.The storm was devastating on the horses of the Grande Armée. Boulart lost ninety draft-horses and seventy of the little ponies of the country by the time he reached Vilna on the June 30. The historian Adam Zamoyski writes:"...the losses for the horses were horrific. Most of the artillery units lost 25 per cent of theirs that night, and the situation in the cavalry was not much better... It is generally estimated that the combat units lots over 10,000 in a period of less than twenty-four hours." [2] Armand de Caulaicourt recalled: "Exhaustion, added to want and the piercing cold rains at night, killed off ten thousand horses."[3] The weather had gone from extremes. The heat of the first days was replaced by the freezing rain of the night of June 29. The loss of the horses meant that the army was to be hampered in moving much needed supplies. The effect on the morale of the troops was also significant. Men spoke of the storm as an omen that foretold of disasters to come.

The fourth Bulletin De La Grande Armée dated June 30, 1812 says nothing of the deteorating situation and is reproduced below.

June 29 1812: Sarah Siddons Leaves the Stage

On June 29, 1812, Sarah Siddons, the great actress takes leave of the stage, playing Lady Macbeth. At end of her sleep walking scene, the audience refused to allow the play to continue. The curtain was drawn. Tumultuous applause continued. Then the curtain rose again to reveal Siddons dressed in white, seated at a table. The audience applauded and she came forward and read a poetical farewell speech. John Cam Hobhouse was present. He writes briefly about it in a less than enthusiastic manner:

On June 29, 1812, Sarah Siddons, the great actress takes leave of the stage, playing Lady Macbeth. At end of her sleep walking scene, the audience refused to allow the play to continue. The curtain was drawn. Tumultuous applause continued. Then the curtain rose again to reveal Siddons dressed in white, seated at a table. The audience applauded and she came forward and read a poetical farewell speech. John Cam Hobhouse was present. He writes briefly about it in a less than enthusiastic manner:She made a poetical farewell speech, written by Horace Twiss – play stopped after her last scene, pit waved hats – I went in to the Pit – almost killed getting in. House filled from top to Bottom with all the rank of London – Sheridan in the orchestra – Mrs Siddons affected – but Kemble more so – never go in pit again. It had not been planned to finish the performance at Act V scene i (the Sleepwalking scene); but, after Siddons’ farewell address, Kemble (her brother) stepped forward weeping and asked the house whether it wanted the show to go on, and the house indicated that it didn’t.

Siddons would continue to appear on the stage even after her farewell performance but with less success. One writer noting: "During the latter years of her professional life, however, she became unwieldy in person, and stagy, heavy, and monotonous in style; when she appeared for the last time in 181 7, as Lady Randolph, no spark of that superlative genius, over which Hazlitt rhapsodised, lit up the performance." Her Farewell Address spoken on June 29 1812 is reproduced below.

June 29 1812: Jefferson to Madsion

On June 29, 1812, Thomas Jefferson is writing to the President of the United States James Madison offering more advice on how to prosecute the war. He calls again for conquest of Canada. He also suggests building pilot boats to be deployed in great numbers on the coast. He writes: "Why should not we then line our coast with vessels of pilot-boat construction, filled with men, armed with cannonades, and only so much larger as to assure the mastery of the pilot boat?" Jefferson's letter is reproduced below.

June 29 1812: Americans Ordered Out of Quebec

On June 29, 1812, the following proclamation was issued requiring Americans to quit the City of Quebec:

Whereas authentic intelligence has been received that the Government of the United States of America did, on the 18th instant, declare war against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and its dependencies, Notice is hereby given, that all subjects or citizens of said United States, and all persons claiming American citizenship, are ordered to quit the City of Quebec on or before TWELVE o’clock at Noon on WEDNESDAY next and the District of Quebec on or before 12 o’clock at Noon on FRIDAY next, on pain of arrest.Ross Cuthbert

C.Q.S. & Inspector of Police

The Constables of the City of Quebec are ordered to assemble in the Police Office at 10 oclock to-morrow morning to receive instructions. Quebec, 29th of June 1812

June 28 1812: Southey's Most Wicked Cold

On June 28 1812, Robert Southey writes to his friend and member of parliament, Grosvenor Charles Bedford. Southey is recovering from a cold but is still busy, as always, writing which he must to support his family, and, on occasion, Coleridge's family. He writes that he does not want to discuss politics but proceeds to do just that. He is upset with the government for "truckling to America" by repealing the Orders in Council. He continues into a rant against the Irish and Catholic Emancipation. Southey's letter is reproduced below.

June 28 1812: Jefferson Contemplates Burning London

On June 28, 1812, Thomas Jefferson writes to General Thaddeus Kosiusko to tell him that war has commenced against Great Britain. Kosiusko was a Polish nationalist, who had served with great distinction as a military engineer with the American army during the revolution. He was a good friend of Jefferson. Jefferson's letter is of interest because Jefferson writes in an imaginative and cold blooded way about his views on how to fight the war with Britain. Jefferson assumes that Britain will be supreme at sea. He can speak with some authority on this as he was responsible for having gutted the American navy. Jefferson writes: "Our present enemy will have the sea to herself, while we shall be equally predominant at land, and shall strip her of all her possessions on this continent. She may burn New York, indeed, by her ships and congreve rockets, in which case we must burn the city of London by hired incendiaries, of which her starving manufacturers will furnish abundance." There is an outlandishness to Jefferson's suggestions but also an imaginative ruthlessness that would probably have made him a far superior war president than James Madison. In this regard, it has to be acknowledged that Madison set the bar rather low. Jefferson's letter to o General Thaddeus Kosciusko is reproduced below.

On June 28, 1812, Thomas Jefferson writes to General Thaddeus Kosiusko to tell him that war has commenced against Great Britain. Kosiusko was a Polish nationalist, who had served with great distinction as a military engineer with the American army during the revolution. He was a good friend of Jefferson. Jefferson's letter is of interest because Jefferson writes in an imaginative and cold blooded way about his views on how to fight the war with Britain. Jefferson assumes that Britain will be supreme at sea. He can speak with some authority on this as he was responsible for having gutted the American navy. Jefferson writes: "Our present enemy will have the sea to herself, while we shall be equally predominant at land, and shall strip her of all her possessions on this continent. She may burn New York, indeed, by her ships and congreve rockets, in which case we must burn the city of London by hired incendiaries, of which her starving manufacturers will furnish abundance." There is an outlandishness to Jefferson's suggestions but also an imaginative ruthlessness that would probably have made him a far superior war president than James Madison. In this regard, it has to be acknowledged that Madison set the bar rather low. Jefferson's letter to o General Thaddeus Kosciusko is reproduced below.June 27 1812: Brock Orders

On June 27 1812, Major General Brock in Upper Canada issues the following orders:

District General Order.

Niagara 27th June, 1812.

No. 1. Colonel Proctor will assume the command of the troops, between Niagara and Fort Erie. The Honorable Colonel Glaus will command the militia, stationed between Niagara and Queenston; and Lieut.-Colonel Clarke from Qneenston to Fort Erie.

No. 2. The Commissariat, at their respective posts, will ration and fuel, for the numbers actually present; the Car Brigade horses, and those of the Provisional Cavalry are included in this order. Officers commanding corps or detachments, will sign the necessary certificates previous to issuing the rations.

3. The detachments of the 41st Regiment stationed at the two' and four-mile points, will be relieved by an equal number of the 1st Lincoln Militia to bring blankets with them on service.

4. The troops will be kept in a constant state of readiness for service, and Colonel Proctor will direct the necessary guards and patrols, which are to be made down the bank, and close to the water's edge.

5. Lieut.-Colonel Nicholl is appointed Qr. -Master General to the militia forces, with the same pay and allowances as those granted to the Adjutant General.

By order of the Major-General,

(Signed) Thos. Evans, B. Major.

June 26 1812: Napoleon at Kovno

On June 26, 1812, Tsar Alexander leaves Vilna. Russian troops are evacuated. The bridge over the river Vilia is destroyed. Military stores in the city are set on fire. Napoleon made his headquarters at an old Russian convent near Kovno. He stays the day to speed up the passage of men over the Neimen, and accelerate their movement in all directions. The Third Bulletin De La Grande Armée dated June 26, 1812 is published and is reproduced below.

June 26 1812: Abner Hubbard Conquers Canada

On June 26, 1812, Secretary of War Eustis orders General Dearborn to proceed to Albany to support General Hull in his offensive operations and invade Canada. They are to move in the direction of Niagara, Kingston and Montreal. Eustis writes:

Having made the necessary arrangements for the defence of the sea-coast, it is the wish of the President that you should repair to Albany and prepare the force to be collected at that place for actual service. It is understood that being possessed of a full view of the intentions of Government, and being also acquainted with the disposition of the force under your command, you will take your own time and give the necessary orders to the officers on the sea-coast. It is altogether uncertain at what time General Hull may deem it expedient to commence offensive operations. The preparations it is presumed will be made to move in a direction for Niagara, Kingston, and Montreal. On your arrival at Albany you will be able to form an opinion of the time required to prepare the troops for action.

Dearborn will delay in moving against Canada.

Meanwhile, on the same day, an American innkeeper Abner Hubbard, two men and a boy row out from Mullin's Bay in New York towards Carleton Island in the St. Lawrence River. The British have Fort Haldimand on the island. The island was supposed to have been ceded to the Americans under Jay's Treaty. On June 26, Abner Hubbard takes matters into his own hands. He leads his small force onto the island, captures the fort and takes the inhabitants as prisoners. No one is hurt in his invasion. His prisoners are also the first prisoners of the war. The island, which is about 2.8 square miles, will be retained by the Americans after the war. In 1817, it is annexed by the state of New York after objections from the British. Carleton Island is arguably the only territory acquired by any of the combatants in the War of 1812. Abner Hubbard succeeded in his invasion and in the conquest of part of Canada where Generals Hull and Dearborn failed.

June 26 1812: Russell's Good Understanding

On June 23, 1812, Jonathan Russell, the American diplomat in London, meets with Lord Castlereagh in the morning to further discuss the repeal of the Orders in Council. Later, Russell writes a letter advising that he is sending the documents and new information to his government. He hopes that this "may accelerate a good understanding on all points of difference between the two States." Russell's letter is reproduced below.

June 25 1812: Lord Byron's Unexpected Honour

On June 25 1812, Lord Byron writes to Lord Holland about his meeting with the Prince of Wales, who was also the Prince Regent and would become George IV on the death of his now incapacitated father, George III. Byron was attending an evening party thrown in London by Miss Johnston [1]. The Prince learned that Byron was present and asked to meet him. Byron was still being lionized for the publication of his poem Childe Harold. Byron was also the subject of increasingly scandalous gossip over his affair with Lady Caroline Lamb. The Prince Regent, notorious for his own affairs, may have been intrigued both by Byron's scandalous reputation and his literary fame. Still the meeting could have been very awkward but fortunately the Prince was not aware of the abuse that Byron had directed at him. On March 7, 1812, Byron had published anonymously, in the Morning Chronicle, a small poem entitled Lines to a Lady Weeping. The poem was a rather vicious attack on the Prince for having abandoned the Whigs. When they did meet, Byron brazenly engaged the Prince in some pleasant conversation about poetry. Byron was flattered when the Prince praised his poem. They also discussed Greek poetry and the poetry of Sir Walter Scott, the Prince's favourite. Byron now writes on June 25 to Lord Holland in a very sarcastic tone about being a court favorite and the possibility of being named the poet laureate. He writes: "I have now great hope, in the event of Mr. Pye’s [2] decease, of ‘warbling truth at court,’ like Mr. Mallet of indifferent memory.—Consider, 100 marks a year! besides the wine and the disgrace; but then remorse would make me drown myself in my own butt before the year’s end, or the finishing of my first dithyrambic.—So that, after all, I shall not meditate our laureate’s death by pen or poison." Byron's letter to Lord Holland is reproduced below.

June 25 1812: News of WAR reaches Canada

On June 25, 1812, news that war has been declared reaches Upper Canada and Lower Canada. In Quebec City, Sir George Prévost, the Governor General and commander of the British forces in Canada, learns of the declaration of war from a Mr. Richardson on an express for the North West Company. Anne Prévost, Sir George Prévost's seventeen year old daughter, made an entry in her diary for that day:

On June 25, 1812, news that war has been declared reaches Upper Canada and Lower Canada. In Quebec City, Sir George Prévost, the Governor General and commander of the British forces in Canada, learns of the declaration of war from a Mr. Richardson on an express for the North West Company. Anne Prévost, Sir George Prévost's seventeen year old daughter, made an entry in her diary for that day:I was summoned in the midst of my French lesson to hear some news that had arrived. It was indeed an important piece of intelligence:–'America has declared War against England.' The news had arrived by an Express to some of the Quebec merchants. ...On this day I saw nothing before me but my Father's honour and glory. Although I knew how small a force we had to defend the Canadas, such was my confidence in his talents and fortune, that I did not feel the slightest apprehension of any reverse. I thought those abominable Yankees deserved a good drubbing for having dared to think of going to War with England, and surely there was no harm in rejoicing that the War had happened during my Father's Administration, because I thought he was the person best calculated to inflict on the Yankees the punishment they deserved.

Colonel Edward Baynes, on the staff of Sir George Prévost, immediately writes to Major General Brock in Upper Canada. Baynes advises Brock that Prévost has just learned of the declaration of war. He writes that Prévost will render "every efficient support in his power" but cannot send any additional troops. Baynes' letter is reproduced below.

-2.png/220px-Isaac_Brock_portrait_1,_from_The_Story_of_Isaac_Brock_(1908)-2.png) Meanwhile, the news of war has also arrived in Upper Canada. On one account, Brock and officers of the 41st Regiment were at Fort George hosting a dinner with their American counterparts from Fort Niagara when the news arrived. The proclamation of war was read. It is said that the men then continued their meal ending with toasts to both King George III and President James Madison and departing cordially.

Meanwhile, the news of war has also arrived in Upper Canada. On one account, Brock and officers of the 41st Regiment were at Fort George hosting a dinner with their American counterparts from Fort Niagara when the news arrived. The proclamation of war was read. It is said that the men then continued their meal ending with toasts to both King George III and President James Madison and departing cordially. June 24 1812:Napoleon Crosses the Niemen

On June 24 1812, in the morning, Napoleon's Grande Armée crosses the Niemen River and the invasion of Russia begins. Philippe-Paul de Segur [1], an eyewitness, describes the scene:

Enthusiasm ran so high that two divisions of the vanguard, contending for the honor of crossing first, almost came to blows and were restrained with difficulty. Napoleon was impatient to set foot on Russian territory. Without faltering he took that first step toward his ruin. He stood for a time at the head of the bridge, encouraging the soldiers with his look. All saluted him with their usual Vive l’Empereur! They seemed more excited than he; perhaps his heart was heavy with the responsibility of so great an aggression, or his weakened body could not bear such excessive heat, or perhaps he was simply disconcerted at finding nothing to conquer.

At length, overcome by impatience, he suddenly galloped off across country and plunged into the forest which skirted the river. He urged his horse on at top speed. In his eagerness it seemed as though he wanted to overtake the enemy all by himself. He rode on in that direction for more than a league without encountering a living soul. Finally he had to turn back to the bridges whence, accompanied by his guard, he descended the river toward Kovno....

...the only enemy that encountered that day or on the follow days was the heavens. Indeed, the Emperor had hardly crossed the river when the air was shaken by a faint rumble. In a short time the sky had grown black, the wind had risen, bringing to our ears the sinister crash of thunder. The threatening sky, this land without visible shelter, threw gloom over our spirits. Several of our men, recently enthusiastic, were terrified as though this were an ill omen. They fancied that fiery clouds had piled up over our heads and were bursting on this country to prevent our entering it...

That same day a more personal misfortune was added to these general trials. Above Kovno, Napoleon was annoyed to find that the bridge over the Viliya had been destroyed by the Cossacks, preventing Oudinot from crossing. He shrugged this off scornfully, as he did everything that thwarted him, and ordered a squadron of Poles to ford the river. These picked troops obeyed without a moment's hesitation.

At first they advanced in order, and when they were beyond their depth they still forged manfully ahead. They swam together to the middle of the stream, but there the swift current swept them apart. Then their horses took fright. Helplessly adrift, they were carried along by the violence of the current. They no longer tried to swim and lost headway completely. Their riders splashed and floundered in vain. Their strength failed, and finally they gave up the struggle. Their doom was certain; but it was for their country and her liberator that they were sacrificing themselves. As they were about to go down, they turned toward Napoleon and shouted: “Vive l’Empereur!” We noticed three in particular who, their mouths still above water, repeated the cheer and immediately sank. The army was gripped with horror and admiration.

Notes

1. Defeat: Napoleon's Russian Campaign (New York Review Books Classics) by Philippe-Paul de Segur (Author), J. David Townsend (Translator), Rk Danner (Introduction), PAGES 2-9.

June 23 1812: Foster Meets Madison and Monroe

On June 23 1812, Augustus Foster, the British Minister has a final meeting with President Madison and subsequent meeting with James Monroe. Foster records what transpired in Minutes that are reproduced below. Foster pressed Madison to agree that if the Orders in Council were repealed that this would be sufficient to end the war. Madison hedged but said, according to Foster,"if the Orders in Council were revoked, and a promise of negotiation given on the question of impressment, it would suffice; that we could not, perhaps, do more on the latter at present, than offer to negotiate." Foster also understood that the President wanted to "avoid as much as possible, pushing matters to extremity." Madison would not agree to an armistice to allow for negotiation.

On June 23 1812, Augustus Foster, the British Minister has a final meeting with President Madison and subsequent meeting with James Monroe. Foster records what transpired in Minutes that are reproduced below. Foster pressed Madison to agree that if the Orders in Council were repealed that this would be sufficient to end the war. Madison hedged but said, according to Foster,"if the Orders in Council were revoked, and a promise of negotiation given on the question of impressment, it would suffice; that we could not, perhaps, do more on the latter at present, than offer to negotiate." Foster also understood that the President wanted to "avoid as much as possible, pushing matters to extremity." Madison would not agree to an armistice to allow for negotiation.June 23 1812: Orders in Council are Repealed

On June 23, 1812, the British government revoked the Orders in Council. On the same day Jonathan Russell in London received two letters from Lord Castlereagh announcing the formal revocation. The Orders in Council had been a response to France's Berlin and Milan Decrees which prohibited British and neutral ships that went to Britain from shipping their cargo to any European port under French control. In turn, the British Orders in Council prohibited British and neutral shipping from carrying goods to the European continent unless they first stopped in a British port and paid for a special licence. The Orders in Council had been unpopular in the United States and also to manufacturing interests in Britain. The change in British policy meant that one of the main complaints that occasioned the War of 1812 is resolved. Lord Castlereagh's letters and the Prince Regent's order are reproduced below.

June 22 1812: Start of War of Poland

On June 22, 1812, Napoleon orders the publication of the second Bulletin De La Grande Armée announcing the start the Second War of Poland. Napoleon tries to blame the war on Russia's supposed intransigence and its demand that French forces evacuate behind the Rhine. Napoleon states that the Russian Ambassador in Paris, Prince Kurakin, had declared "he would not enter into any explanation before France had evacuated the territory of her own allies in order to leave them at the mercy of Russia." Napoleon adds that the France's own ambassador to St Petersburg had been denied an audience with the Tsar when he attempted to negotiate peace. Napoleon's Bulletin is extraordinarily clever but self serving. It fails to explain why it happens that the French army was in such numbers on the Russian border in the first place. He ends the Bulletin with a stirring call to arms to his soldiers. The second Bulletin De La Grande Armée of June 22, 1812 is reproduced below.

June 22 1812: Madison to Jefferson

On June 22, 1812, President Madison writes to Thomas Jefferson enclosing "paper containing the Declaration of War, which is probably the Proclamation of June 19, 1812. Madison goes on to writes "It is understood that the Federalists in Congress are to put all the strength of their talents into a protest against the war, and that the party at large are to be brought out in all their force." Madison has also just learned about the assassination of the British Prime Minister Perceval which occurred on May 11, 1812. He is unaware that Liverpool has already formed a new government. Madison's letter is reproduced below.

June 21 1812: Personal Good Wishes and War

On June 21 1812, there is a further flood of letters exchanged between Augustus Foster, the British Minister in America, and Secretary of State James Monroe. Foster had been told by Monroe about the declaration of war earlier but it on the 21st that he receives official notification of war with the receipt of President Madison's Proclamation. In his letter of today, Monroe adds: "In announcing to you this event which terminates your official relations with this Government, I will not withhold the expression of the respect and good wishes which you have personally inspired, and which are still extended to you." Foster is being told nicely that he must leave. Foster is already making arrangements to depart but he is anxious to reach an agreement to allow the exchange of mail to continue between the two countries. Monroe advises him that this issue is before Congress. Foster is also concerned that the British ship arriving with the two survivors of the Chesapeake will not be fired on. He also wants to ensure that this does not happen to the ship he will need to depart. The various letters are produced below.

On June 21 1812, there is a further flood of letters exchanged between Augustus Foster, the British Minister in America, and Secretary of State James Monroe. Foster had been told by Monroe about the declaration of war earlier but it on the 21st that he receives official notification of war with the receipt of President Madison's Proclamation. In his letter of today, Monroe adds: "In announcing to you this event which terminates your official relations with this Government, I will not withhold the expression of the respect and good wishes which you have personally inspired, and which are still extended to you." Foster is being told nicely that he must leave. Foster is already making arrangements to depart but he is anxious to reach an agreement to allow the exchange of mail to continue between the two countries. Monroe advises him that this issue is before Congress. Foster is also concerned that the British ship arriving with the two survivors of the Chesapeake will not be fired on. He also wants to ensure that this does not happen to the ship he will need to depart. The various letters are produced below. June 20 1812: Hanson Denounces the War

On June 20, 1812, two days after war was declared, Alexander C. Hanson, publishes in his Baltimore newspaper, the Federal Republican, an editorial denouncing the war. He writes, in part, as follows:

Without funds, without taxes, without a navy, or adequate fortifications – with one hundred and fifty millions of our property in the hands of a declared enemy, without any of his in our power, and with a vast commerce afloat, our rulers have promulgated a war against a clear and decided sentiment of a vast majority of the nation....We mean to use every constitutional argument and every legal means to renders as odious and suspicious to the American people, as they deserve to be, the patrons and contrivers of this highly impolitic and destructive war; in the the fullest persuasion that we shall be supported and ultimately applauded by nine-tenths of our countrymen, and that our silence would be treason to them...

...We shall cling to the rights of freemen, both in act and opinion, till we sink with the liberties our country, or sink alone. We shall hereafter, as heretofore, unravel every intrigue and imposture which has beguiled or may be put forth to circumvent our fellow citizens into the toils of the great earthly enemy of the human race. We are avowedly hostile to the presidency of James Madison, and we will never breathe under the dominion, direct or derivative, of Bonaparte, let it be acknowledged when it may. Let those who cannot openly adopt this confession, abandon us, and those who can we shall cherish as friends and patriots, worthy of the same.

June 20 1812: Let their Destinies be Fulfilled

On June 20, 1812, Napoleon is at Gumbinnen, where he receives a courier from St Petersburgh advising him that his ambassador Count Lauriston has been refused an audience with the Tsar and forbidden to travel to Vilna. The Tsar has also asked him and other diplomats, who are allies of France, to call for their passports "which amounted to a declaration of hostilities." [1]Napoleon now orders the publication of the first of various bulletins to be issued as part of his propaganda war against Russia. He also orders the army to march for the purpose of passing the Niemen. "The conquered assume the tone of conquerors: fate drags them on; let their destinies be fulfilled," Napoleon is supposed to have said or wished to be remembered as having said. Napoleon's First Bulletin of the Grand Army of June 20, 1812 is reproduced below.

June 20 1812: Life, Liberty and Property for Canadians

On Saturday, June 20, 1812, in an Executive session, which meant that it was held in secret, the United States Senate receives a message from the House of Representatives asking the Senate's concurrence for a proposed Presidential proclamation. The House's resolution would authorize the President to issue a proclamation to the inhabitants of the British American Continental Provinces. The Proclamation would provide that the inhabitants of Upper and Lower Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have "full enjoyment of their lives, liberty, property, and religion, in as full and ample manner as the same are secured to the people of the United States by their constitution." The resolution read as follows:

June 19 1812: John Quincy Adams Discusses Napoleon

On June 19, 1812, John Quincy Adams, the American Ambassador to Russia in St. Petersburg, pays a visit to his French counterpart. Adams writes, in part, in his diary:

I asked him where the Emperor Napoleon was. He did not know — perhaps at Warsaw. He heard the Russians had concentrated their forces, because they said the Emperor Napoleon always attacks the centre. "There it is!" said he." They think because he has done so before, he will do so again. But with such a man as that, they will find their calculations fail them. He will do something that they do not expect. He does not copy himself nor any other. He does something new."

June 19 1812: A Proclamation and a Warning

On June 19, 1812, President Madison issues a Proclamation exhorting Americans to "be vigilant and zealous in discharging" their duties in the war that has now been declared against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and its dependencies. He appeals to the love Americans have for their country, and "as they value the precious heritage derived from the virtue and valor of their fathers." Madison ends with the hope that the United States will obtain a "speedy, a just, and an honorable peace."

On the same day, Senator Obadiah German of New York, a strong opponent of the war, gives a speech where he warns: "After the war is once commenced…I presume gentlemen will find something more forcible than empty war speeches will be necessary." He adds that he has acted "to check the precipitate step of plunging [the] country prematurely into a war, without any of the means of making the war terrible to the enemy; and with the certainty that it will be terrible to ourselves." Madison's Proclamation is reproduced below.

On the same day, Senator Obadiah German of New York, a strong opponent of the war, gives a speech where he warns: "After the war is once commenced…I presume gentlemen will find something more forcible than empty war speeches will be necessary." He adds that he has acted "to check the precipitate step of plunging [the] country prematurely into a war, without any of the means of making the war terrible to the enemy; and with the certainty that it will be terrible to ourselves." Madison's Proclamation is reproduced below.

June 18 1812: WAR

|

Senator Varnum reports back to the Senate that the President had signed into law the war act. He then moved a motion to lift the "injunction of secrecy" on the issue of war that has applied since the President delivered his confidential message on June 1, 1812. The motion passes and the doors of Congress are now opened to a country at war.

June 17 1812: Jefferson and the Common Law

On June 17 1812, Thomas Jefferson writes to Judge John Taylor about the common law. Jefferson's letter highlights that, aside from his many other areas of expertise, Jefferson was also a very fine lawyer. In the letter, Jefferson is at pains to give an American foundation to law based on the rights of men as opposed to what he views as the more narrow British "common law rights" He writes: "...the application of the common law to our present situation, I deride with you the ordinary doctrine, that we brought with us from England the common law rights. This narrow notion was a favorite in the first moment of rallying to our rights against Great Britain. But it was that of men who felt their rights before they had thought of their explanation. The truth is, that we brought with us the rights of men; of expatriated men." As Jefferson continues he is forced to concede that the common law has been adopted in America but he draws the line at relying on any British authorities from after the Declaration of Independence. He would have preferred to have had a civil code as a opposed to a judge based common law. This letter reflects many of the ongoing tensions of American jurisprudence at their most basic and original foundations. Jefferson's full letter is reproduced below.

June 17 1812: Senate Votes for War

On June 17, 1812, a Wednesday, the United States Senate is again considering the third reading of a bill from the House of Representatives, which is entitled "An act declaring war between Great Britain and her dependencies, and the United States and their territories."

Senator Giles brings a motion that the war bill be recommitted to the select committee of Senator Anderson with instructions to modify it to authorize only for naval reprisals against both Britain and France. His motion is put to a vote and is defeated with yeas 14 and nays 18.

Senator Horsey then brings a motion to adjourn the Senate. His motion is defeated.

Then the main question is put: Shall this bill pass as amended? The vote is taken and it is determined in the affirmative with 19 yeas and 13 nays. So it was resolved that by six votes that the United States would go to war. The title of the bill is amended to "An act declaring war between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their territories."

Senator Anderson then brings a motion that a committee be appointed, to consist of two members, to carry the war bill to the House of Representatives and ask for their concurrence in the amendments. Senators Anderson and Varnum were chosen to be the committee.

June 16 1812: Orders in Council to be Repealed

On June 16, 1812, Henry Brougham brings a motion in the British House of Commons to repeal the Orders in Council. He speaks at length and eloquently for their repeal. His motion and speech come after six weeks of committee hearings on the issues of the Orders in Council. Lord Castlereagh, the new leader in the House of Commons, responds that the new government of Lord Liverpool has decided to suspend the Orders in Council. Castlereagh adds that the repeal of the Orders is conditional on the United States lifting its embargo. This condition is not considered to be significant as the British understand that the Americans would agree. The change in British policy means that one of the main complaints that occasioned the War of 1812 is resolved, for all practical purposes, prior to the war being started. The American government will not learn of the repeal in time given the distance that the news has to travel across the Atlantic. In two days, on June 18, 1812, James Madison will declare war on Great Britain and her dependencies. Time and distance causing or at least contributing to the war between the two countries. Extracts from Henry Brougham's speech are reproduced below. The full speech can be found here.

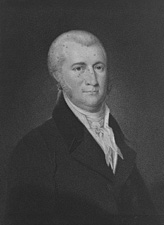

June 16 1812: Senator Bayard Delays War Bill

On June 16. 1812, the opponents of the war bill in the Senate try to delay it from being passed. On this day, the charge is being led by Senator James A. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was a strong opponent of declaring war but once war was called he strongly supported its vigorous prosecution. President Madison would later choose Bayard as the only Federalist to be one of the peace commissioners that negotiated the Treaty of Ghent ending the war. After the peace negotiations, Bayard would leave Europe in 1815, become ill on the voyage home and die five days after his return.

On June 16. 1812, the opponents of the war bill in the Senate try to delay it from being passed. On this day, the charge is being led by Senator James A. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was a strong opponent of declaring war but once war was called he strongly supported its vigorous prosecution. President Madison would later choose Bayard as the only Federalist to be one of the peace commissioners that negotiated the Treaty of Ghent ending the war. After the peace negotiations, Bayard would leave Europe in 1815, become ill on the voyage home and die five days after his return.

On June 16, 1812, Senator Bayard is using every parliamentary trick to try and stop the declaration of war. He first brings motion to postpone the further consideration of the war bill to the thirty-first day of October. The motion is defeated with 11 yeas to 21 nays.

Senator Bayard then brings a motion to postpone the further consideration of the bill to the third day of July next. Again, the motion is defeated, 9 yeas to 23 nays. Undaunted, Senator Bayard brings a third motion to postpone the further consideration of the war bill to Monday next. Again, the motion is defeated, yeas 15 and nays 17. Unsuccessful, on his motions Senator Bayard has nevertheless delayed the passage of the war bill for another day. A motion is then brought to adjourn the Senate. This motion is successful, yeas 18 t0 14 nays. The Senate adjourned to 11 o'clock to-morrow morning.

June 15 1812: Senate Passes Third Reading of WAR Bill

On June 15, 1812, the United States Senate resumes consideration of a war bill. The Senate first considers a motion by New York Senator Obadiah German to postpone any further dealing with the bill until the first Monday of November. Senator German is a strong opponent of the war. On June 13, 1812, he had forcibly and presciently argued that the country was not ready for war. In particular, he had argued that the use of militia to prosecute the war would be disastrous. He argued "the evils of attending upon calling a large portion of the militia into actual service for any considerable time, is almost incalculable. After a short time, sickness, death, and many of the evils will teach you the impropriety of relying on them for carrying on the war." Senator German's motion to postpone the further consideration of the war bill until first Monday in November is put to a vote and defeated. His motion is defeated, yeas 10 and nays 22.

Senator Michael Leib of Pennsylvania then brings his motion to try and revive the more extensive amendments that had not passed during the Senate on June 13, 1812. His motion seeks to amend the war bill with nine sections that basically limit the hostilities to a naval war and create legal procedures for salvage rights. Leib also adds a new section nine that extends the naval war to "the Emperor of France and King of Italy or his subjects". Senator Anderson tries to strike out this ninth section but his motion is defeated, yeas 14 and nays 18. Leib's motion is then put to a vote. The question is whether to strike out the original bill after the word "that," and insert the new amendments. The motion is determined in the negative, yeas 15 and nays 17.

One further motion is brought by Senator Lloyd, to amend the bill, by inserting, after the word "that," in the third line, the words "from and after the___ day of___next." The motion is also determined in the negative, yeas 13 and nays 19. This is another attempt to delay by leaving blank the date of any declaration of war.

With the preliminary motions out of the way, the Senate next considers the main motion on the form of the bill that had passed on June 13 1812. A fragile majority had coalesced around this form of the bill which, aside from some minor differences in language, is basically the same as the bill passed by the House. The Senate thus considers whether the House's war bill, as amended on June 13 1812, is to pass to a third reading. The vote is taken and determined in the affirmative, yeas 19 and nays 13. War is coming. The Senate adjourns to 11 o'clock tomorrow morning.

June 14 1812: Wellington Advances on Salamanca

On June 14, 1812, Wellington is leading his Anglo-Portuguese and Spanish armies towards Salamanca in Spain. He is concerned that the French General Marmount will try to concentrate his forces and attack. The main battle between the two forces is still over a month away. It will take place on July 22, 1812. Wellington's dispatches of June 14 1812 are reproduced below.

June 14 1812: Foster to Monroe

On June 14, 1812,* Augustus Foster, indefatigably continues to spill more ink in a desperate and futile attempt to convince Secretary of State James Monroe of the justness of British policy on the Orders in Council. He is answering Monroe's letter of yesterday. Foster's letter is reproduced below.

Foster to Mr. Monroe.

Washington, June 14, 1812. Sir: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 13th inst. It is really quite painful to me to perceive that, notwithstanding the length of the discussions which have taken place between us, misapprehensions have again arisen respecting some of the most important features in the questions at issue between the two countries, which misapprehensions, perhaps, proceeding from my not expressing myself sufficiently clear in my note of the 10th inst. in relation to one of those questions, it is absolutely necessary should be done away.

June 13 1812: Monroe to Foster

On June 13, 1812, a frustrated Secretary of State James Monroe continues to respond to Augustus Foster. He writes that it is impossible for him "to devise or conceive any arrangement consistent with the honor, the rights, and interests of the United States, that could be made the basis, or become the result of a conference on the subject" of the orders in council except their repeal. Nevertheless, he will continue to entertain anything that Foster has to offer but he suggests he should do it in writing as this will provide for the "requisite precision, and least liable to misapprehension". He also urges that it be done "without delay." Monroe's letter is reproduced below.

June 13 1812: Senate's Sundry Amendments to WAR

On June 13, 1812, the Senate resumes its consideration of the House's war bill. It first dealt with the motion by Senator Lloyd for more information from the State Department on Britain and France. The motion is defeated. Presumably all the correspondence and information had been provided. The Senate had been studying the diplomatic issues since June 1.

Senator Gaillard is then requested to take the chair. The Senate next considers the war bill as a committee of the whole on a motion by Senator Anderson. The senators agree to sundry amendments and the President resumes the chair. Senator Gaillard then reports the amendments to the war bill. These are considered and agreed to by the Senate. These amendments include the following:

Third line, after the word "between," strike out to the end of the line, and insert, "the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the dependencies thereof."

Line 4, after the word "states," where it first occurs, insert, "of America."

Line 9, after the word "Britain," strikeout to the end of the bill, and insert, "the said United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the subjects thereof."

Yesterday the Senate had added the word "and' after the word "Britain". The proposed changes (strikeouts in blue and inserts in red the word "and" in green) means the House's war bill reads:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that war be, and the same is hereby, declared to exist betweenHaving done such a great job the Senate decides to adjourn.Great Britain and her dependenciesthe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the dependencies thereof, the United States of America and their territories; and that the President of the United States is hereby authorized to use the whole land and naval force of the United States to carry the same into effect; and to issue to private armed vessels of the United States, commissions, or letters of marque and general reprisal, in such form as he shall think proper, and under the seal of the United States, against the vessels, goods, and effects, of the government of Great Britain and, of its subjects, and of all persons inhabiting within any of its territories or possessions.the said United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the subjects thereof."

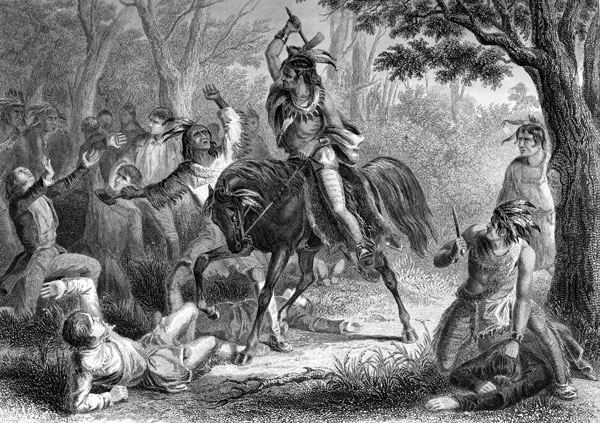

June 13 1812: Report on Indian Hostilities

On June 13 1812, Representative McKee tabled in the House of Representatives the report of his committee investigating the "agency the subjects of the British government may have had in exciting the Indians on the western frontier". The report had been prepared as a result of President Madison's message to Congress of June 1, 1812. Madison's message had referred to the role of British traders and garrisons in encouraging attacks on the frontiers. The widespread fear of these attacks played an important role in exciting Americans to war. The day before the report was tabled, Thomas Jefferson, the sage of the Enlightenment and someone who had written on the nobility of the first nations, is also writing that a conquest of Canada "secures our women and children forever from the tomahawk and scalping knife, by removing those who excite them". The House's report concludes that the British had been very generous in providing provisions to various tribes at Fort Malden. The report concludes from this that "it is difficult to account for this extraordinary liberality, on any other ground than that of an intention to attach the Indians to the British cause, in the event of a war with the United States." The committee's recommendation is that the President call out the militia "to march against and disperse the armed combination under the prophet" referring to Tecumseh's brother, who was believed to be the main Indian leader. The full report is reproduced below.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)